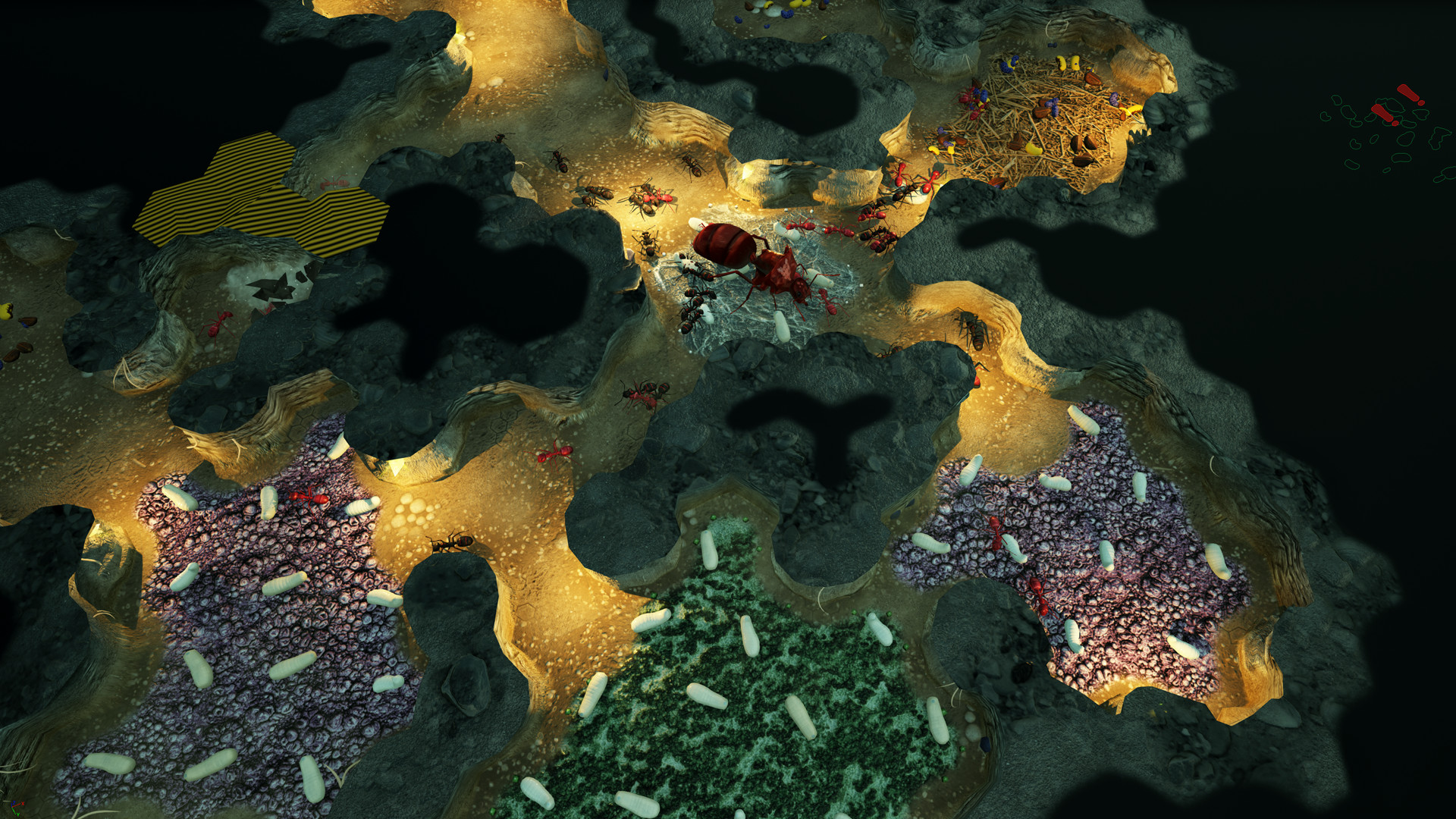

Much of what happens in and around the university cannot come into focus if you see “the university” as a bounded entity. In the undergrowth, education names a wider, more diffuse set of practices of collective sense making and world making than dominant, European, imperialist, and Enlightenment conceptions allow. Moreover, it allows us to ask what it is about education that we are committed to, what it is we want to preserve and protect. Approaching the question of education-which is at once practical and theoretical, ontological and speculative-from an ecological account of institutions, practices, and affective attachments gives us a way of seeing distinct, and perhaps incommensurate, critiques of the university as intimately adjacent. This is, of course a question that has been asked for a very long time, but we ask it today, again, because too many of us have been trained to conflate education with schooling (including at the university) or to accept that education requires institutionalized schools. Beginning with universities-because each contributor to this issue is entangled with them, albeit in differential ways-we aim to go beyond critiques of the institution (although such critiques orient our thinking), 1 toward the project of asking what education is and what it might yet become. The concept of “educational undergrowth” points toward an account of educational practices and institutions that attends to ecologies that are not always visible in dominant (humanist) conceptualizations of what education is and does.

The university, education, abolition, decolonization, ecology

On the other hand, it draws on affect theory, new materialisms, and work in decolonial and critical ethnic studies to valorize otherwise marginal, bewildering, errant educational encounters that are always taking place in the undergrowth of the university. On the one hand, educational undergrowth accounts for how resources circulate unevenly in the colonial ecology so that the “growth” of some people, institutions, and projects is possible only because others are deprived, defunded, and disinvited. The introduction intervenes in contemporary leftist debates about the university in particular and education more generally by offering a way of attuning to critical, abolitionist, and decolonial projects as specific but intraactive outgrowths of the colonial ecology and myriad disruptive projects (happening both in and outside of institutionalized schools). This allows both for critical accounts of how coloniality shapes institutions such as schools and universities, always in relation to many other institutions and sites, and for speculative experiments in queer, decolonial, abolitionist education. In this framing, the university appears as a specific, but not isolated, part of a colonial ecology structured around producing Man. The editors elaborate this ecological view by drawing on theories of coloniality, especially the work of Sylvia Wynter (and her human/Man distinction) and Stefano Harney and Fred Moten (in The Undercommons). This introduction to the special issue “Educational Undergrowth” proposes an ecological view of educational institutions and practices, one that foregrounds the porosity of borders so that entities and institutions that can sometimes seem distinct are thought of as always entangled.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)